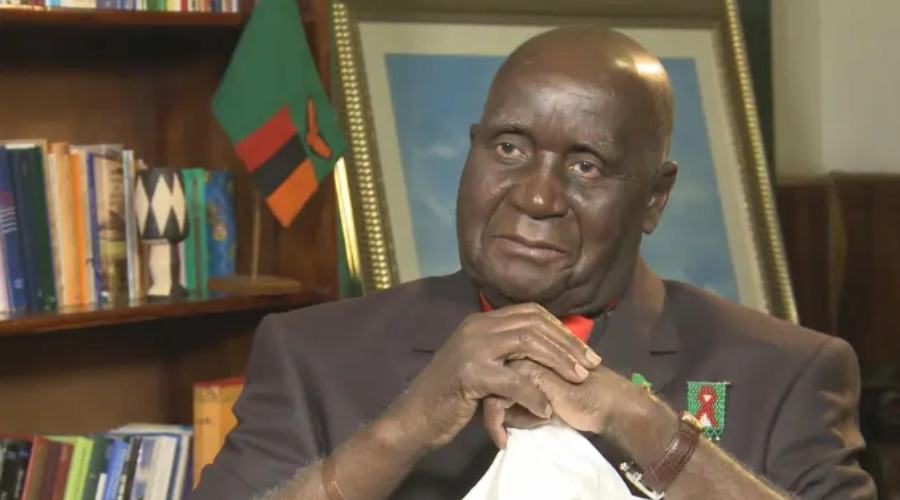

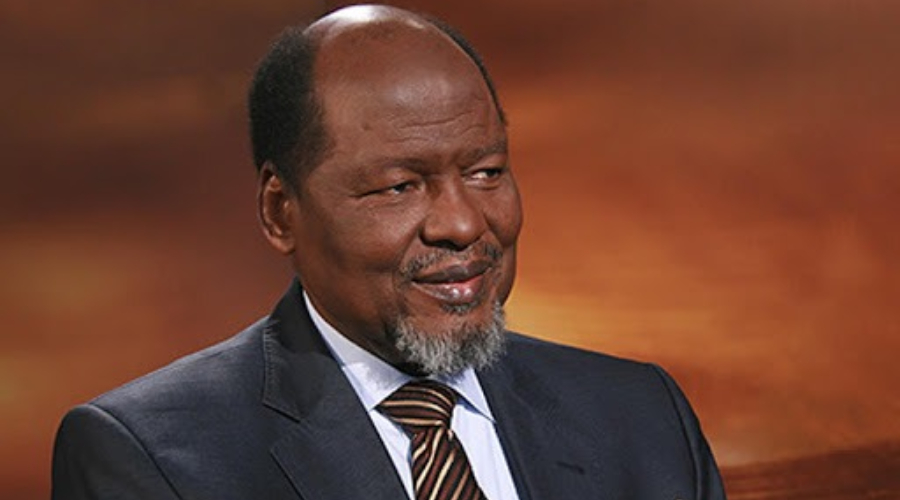

Joaquim Chissano saw Nyerere as a beloved son of Africa

12 - August - 2025

I must say that I was slightly perplexed when I was asked to write something about Julius Nyerere in just two pages. Is it possible to summarize the deeds of one of Africa’s best sons in such a short space? I will do my best. I first began to hear about Nyerere in 1960, as I was finishing secondary education and readying to go to university in Lisbon.

One day I had to accompany a friend to the house of one of our teachers. After we were done, the teacher commented that a group of Mozambicans encouraged by Tanzania’s independence had decided to fight for Mozambique’s. It was later, when we went to France, that we learnt more about figures like Jomo Kenyata of Kenya, or Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, who were fighting for their peoples’ independence.

In Paris, in 1961, we learnt that Dr Eduardo Mondlane, who was not yet the President of FRELIMO, the organisation fighting for Mozambique’s independence, was in contact not just with President Nyerere, but also with Nkrumah and other prominent leaders of that time. Nyerere was encouraging Mondlane to lead the struggle for the liberation of Mozambique. Nkrumah was also trying to convince him. These two important names were leading the movement to support the liberation of other peoples, and had established refugee camps that were also centres for the liberation struggle. In 1963 I moved to Tanzania.

I found Nyerere working to mobilize the Tanzanian people to support the liberation movements, especially FRELIMO. He would organize long marches and demonstrations in support of the different liberation movements. His motto was that no African country could feel free and independent while there was a single country that was not yet independent. His slogans were Uhuru na umoja (independence with unity), Uhuru na Kazi (independence with work) and Uhuru na amani (independence with peace). He did everything within his power to support the liberation of Africa. I remember one mass rally where he asked every Tanzanian to contribute one shilling for the liberation of Mozambique.

The money started to pour in from that moment. I think that one million shillings was soon raised and the process expanded to the rest of Tanzania. From Nyerere I learnt that there are three main foundations for the development of a country: 1st Watu – the people; 2nd Ardhi – the land, and 3rd Uongozi bora – good governance. This last may seem new to many people today but this was already a key concept for Nyerere back in 1965. As a Mwalimu (teacher) he had a didactic way of communicating his profound thoughts, using down to earth language. He found this easy because he had an in-depth knowledge about the culture of his people and its complex diversity. In fact he had travelled the whole country, in some sections on foot, and had slept in the homes of poor people in villages, often on a mat while he was mobilizing the people to claim independence and establishing the grass-root organs of TANU (Tanganyika African National Union).

When FRELIMO was established in 1962, Mondlane was elected president. This was followed by the phase that saw the preparation of the armed struggle for the liberation of Mozambique. Nyerere facilitated contacts with the OAU Liberation Committee established in 1963 and based in Tanzania. He worked to secure support for FRELIMO, both logistic and diplomatic. Algeria, the Soviet Union, and China agreed to train FRELIMO guerrillas and provide material support. Tanzania facilitated travel documentation. At the OAU Nyerere was also a staunch supporter of FRELIMO. This not only helped the start of the struggle, but also its development. When Mondlane arrived in Tanzania, he enjoyed easy access to President Nyerere, who was likeminded. They had a cordial relationship. This did not mean that Nyerere interfered in the decision-making process of the FRELIMO leadership: Mondlane would make the decisions and inform him.

Nyerere always wanted to keep some distance and allow the liberation movements to deal with their independence issues; he would play the supporting role. Following the start of the armed struggle for the liberation of Mozambique, and from 1965 through to 1968, the Tanzanian population was starting to feel the pinch.

There were retaliatory attacks by the Portuguese, mainly in the form of landmines planted along Tanzania’s southern border; they would also stage raids into Tanzania. Nyerere’s response was to exhort the Tanzanian people to stand firm and remain vigilant in their support for the Liberation struggle of Mozambique.

President Nyerere followed the progress of the armed struggle through regular contacts. Whenever Samora Machel, who had taken over the leadership of FRELIMO after Mondlane’s assassination, would come to Dar-es-Salam, Nyerere would meet with him to find out how the war was progressing. And in his army he had a structure that comprised senior officers who also kept him informed. There was also a minister in the President’s Office permanently in contact with us.

Even when we faced difficulties making headway, we knew we could rely on Nyerere to provide momentum to the armed struggle. For example, we faced problems on the Tete front, close to the border with Malawi. The struggle started in 1964, at a time when Malawi was not yet independent, and we had good relations with the Malawi Congress Party led by Hastings Kamuzu Banda, although not directly, as he spent his time between Ghana and England. But the support we had from Malawi was actually a result of the commitment of other leaders there. As a result, we were able to start the armed struggle through Malawi.

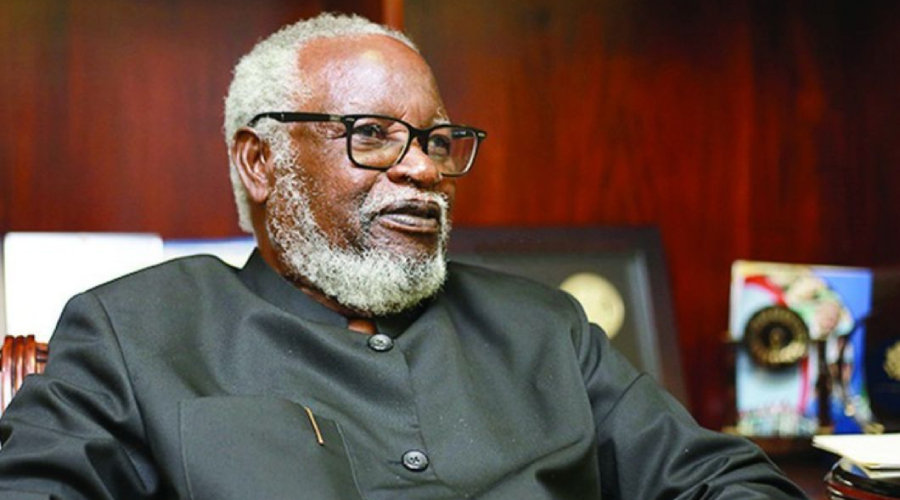

From the Zambian side we also had access. But when Malawi became independent, the landlocked country began to face problems in accessing the sea, which until then had been through Mozambique. Nyerere came up with the idea that we could give it access to the sea through Zambia and on to Tanzania. Nyerere started talks with President Kaunda, and eventually this culminated in the creation of what came to be known as the Front Line States, and later on the Southern African Development Community. President Kaunda accepted this strategy and as a result TAZARA (Tanzania Zambia Railways), linking the two countries was built, and later a paved road was added and subsequently a pipeline (TAZAM). But Malawi believed that the armed struggle was ineffective as it was not possible to overthrow the power of the whites, which created dissention within the Malawian government, and some ministers sought refuge in Tanzania and Zambia.

Malawi closed its borders, so we could no longer operate through Malawi. Zambia had also closed its border, under pressure from British officials who remained for a while in the country immediately after independence in 1965. So we had to wait for better times for Zambia, which came in 1968. I would like to emphasise that President Nyerere was personally committed to the struggle for independence, but that there were limitations to what the country could do.

In Tanzania some voices advocated the direct participation of the Tanzanian armed forces. Young Tanzanian officers were highly emotional about the struggle that we were waging and wanted to join us in the fighting.

Nyerere said: “No, we shall provide every support but not that one”. Nyerere always argued that strengthening logistic support would help us to resist, while at the same time he took every opportunity to denounce at the international level the atrocities committed by the Portuguese.

Nyerere strongly encouraged us to proceed with what we were doing and he was very much aware of our task. In 1973, we started to feel that something was about to change in Portugal, and so we informed Nyerere. He was on guard against the manoeuvres of the Portuguese colonialists who wanted to derail our struggle and lead us towards a sham independence. Nyerere’s role at the OAU when the 44 member states were divided with respect to the recognition of the MPLA as the legitimate representative of the Angolan people was key. “Don’t tell me that Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA is supported by democratic forces.

Can we call apartheid a democratic force that wants to see Angola’s genuine independence?” Nyerere always argued from a socialist position, although he would never talk about applying scientific socialism. But he took it as a direct challenge when FRELIMO said that they believed in scientific socialism. He would say: “You try that to see if it works. But you need to move carefully because there are much more powerful forces, and in the context of the Cold War they will oppose vehemently”. He cited the example of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba, who was murdered because of his open support for communism. But Nyerere never exerted any pressure on FRELIMO to lean towards any particular model after achieving independence. What’s more, he kept out of the peace talks, while supporting our positions. He would joke, “for the moment I will continue with my utopian socialism”. When the defeat of colonialism in Mozambique ushered in a FRELIMO government, Tanzanians celebrated, and Nyerere was undoubtedly the happiest of all Tanzanians, precisely because he had embraced wholeheartedly the struggle of the Mozambican people.

He congratulated us in a way that made it very clear that he felt the victory of the Mozambican people was also the victory of the Tanzanian people. We all felt as if Tanzania was being liberated a second time. And we could count on Mozambique as yet another liberation force for the other countries: Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Namibia. Even after leaving office, Nyerere continued to be interested in the consolidation of independence, restoring peace, and fostering national unity in countries ravaged by violent conflicts.

We saw the crucial role he played in Uganda and Burundi, where he invited the Mozambican government to make a contribution towards peace and reconciliation. I recall visiting President Nyerere at his home with President Samora, as we were preparing to return and put in place a transitional Government as envisaged in the Lusaka Agreement.

Nyerere insisted on the need for FRELIMO to strive to uphold National Unity; he insisted that we should not act emotionally; we should understand the Mozambican reality and take the best decision toward creating a government that would earn the trust of the Mozambican people. If I were asked to define Julius Nyerere, the man, I would say that he was an intellectual with a very profound understanding of the African reality; its need for independence, development and unity. He was also a man of the people. He was always a joyous person, with a happy and easy smile. Even when we were discussing serious matters he would find a moment to smile, even to the point of making others smile, and then we would go back to serious business.

Mwalimu Nyerere was also a simple man. When we went to see him at his home in Butimand we found him harvesting cotton on the family farm, with a bag on his back. President Samora turned to the Tanzanians that were with us and asked if indeed this is how they wanted their leader to live. They looked at one another. Later on they built him a house. He was not concerned with luxury, even though he was the son of a traditional chief. He led a simple life. He was a man that always learnt from interacting with other people; he was respectful.

I continued to enjoy a good relationship with President Nyerere, despite our age difference and very different positions. He would always listen to what I had to say and would respect my arguments. He was hurt by the signing of the 1984 Nkomati Agreement on non-aggression between Mozambique and South Africa: it seemed to him a betrayal of the national liberation struggle. But later on he came to understand why we did it, in the same way that the ANC came to understand our predicament. He understood that there was no other way to give us some breathing space and enable us to think about the best forms to support the national liberation struggle in other African countries.

Nyerere was one of the best sons and leaders of Africa. He had a big heart. He was able to recognize that his beloved Africa had not been true to its democratic ideals along the way to independence, and that the continent was fertile ground for coup d’états and dictatorships and that while colonialism was to blame to a certain extent, Africans should also accept their share of responsibility: “We cannot say that as African leaders we always practice good governance. It is now time for us to correct our mistakes.”

BY JOAQUIM ALBERTO CHISSANO

Former President of Mozambique

(source: www.juliusnyerere.org)