Mshigeni: First Tanzanian scientist to introduce seaweed farming in Africa

Largest complex for marine research in Africa based in Namibia named after him

Education is the passport to the future for tomorrow belongs to people who prepare for it today - Malcom X.

If you want to know that a certain country is on track towards development, just find out how many scientific research papers that country is producing per year. It may not also be bad to look at what the budget a country allocates to research. In 2005, Harvard University produced more scientific papers than African and Middle East countries put together. In Africa, we have very few outstanding scholars who have excelled in research. One of them is Prof Keto Mshigeni. He is an honouree professor who has attained the mark of recognition.

He is an inspirational Tanzanian scientist, who is most respected as a lecturer, mentor and an astute scholar. In the world streets, buildings, wards or even villages are named after politicians, kings, queens, entertainers, but hardly after any scientist who makes our lives easier every day. Prof Mshigeni is the only exemplary, honoured and recognised scientist who has had a mark in the lives of many people.

He is an emblem of humility, a hard worker, a great African teacher of science. When you travel through the Namibian desert to the beautiful Town of Hearts Bay on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, there you find Sam Nujoma Marine and Coastal Resource Centre, a Campus of the University of Namibia. The largest complex for marine research in Africa is named after Prof Mshigeni.

The Professor Keti E. Mshigeni Mariculture Research Complex is the largest in Africa. That is a rare breakthrough in the scholarly arena. His work on seaweeds, mushrooms, medicinal plants, zero emission and zero waste have made him a well-known scholar throughout the world. He has authored several books and research reports and contributed many articles to academic journals.

Prof Mshigeni has navigated through the ladders of education and currently steers Vice-Chancellorship of Hubert Kariuki University of Health Sciences. This still reflects the personality and makeup of Prof Mshigeni who has an exceptional ability to handle tough challenges in life and with a smile, always in high demand in education circles both inside and outside Africa and most importantly has a passionate concern for education and science. Who’s who Tanzania got a rare opportunity of meeting with him and this is what he had to say for his exemplary character:

Who’s who in Tanzania: Professor, the readers of Who’s who Tanzania would like to know who Keto Mshigeni is?

Prof Mshigeni: I grew up in a small village in Ami, a district in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania. I started school in 1952 at Pinchi (Pinji) Primary School, a mission school of the Seventh Day Adventists and later joined Sambweni District for my middle school and Shuji Mission School for my Standard 6 and 7. I went to Form One at Tabora School in Tabora. It was there that I met the likes of Mr Mpopo. He was my classmate. I studied at the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM). At that time it was still part of the University of East Africa. That is to say, I was at the Dar es Salaam Campus of the University of East Africa. I studied Botany, Geography and Education. In fact, after graduation I was posted to go to teach at Old Moshi Secondary School. But Wilbert Chagula, the then Principal at the University of Dar es Salaam told me that I was being groomed for UDSM. I think it was because of the course I had done in the Faculty of Science. Mr Chagula arranged for me to go to Hawaii on a scholarship from Lancra Foundation in 1969. I left for Hawaii in 1970.

Who’s who in Tanzania: There is a saying that a good horse is seen on its birth. What do you consider to be your first signs of success?

Prof Mshigeni: When I was at high school, I conducted my first research on ‘polygamist’ bishop birds. Some birds like doves, are always in bonded pairs - one male and one female – a form of ‘monogamous’ partnership, but some birds are very notorious. In some types one male bird may have up to four female birds, some, of course, have more female birds. One day as I was going to school, I saw in the school compound a variety of birds. One was red and black, others were yellow-brown. I found this to be fascinating. I asked myself how these two species of birds could mix so easily. I reported what I had seen to my Biology teacher Lenox who told me that what I had seen was a ‘polygamist’ bird.

Red and black was the male bird, the three or four yellow-brown birds were female birds.

He then advised me to study further the behavour of those birds since it was part of our Form Six examination. I researched on birds for two years and I recall, by the time I finished Form Six, I had investigated bout 40 nests of this bird. I discovered a lot of things, but most interesting was the way these birds divided their labour. I summarised all my notes after which my teacher sent the essay to Makerere University for a Swineyton Butt competition for schools in East Africa. Swineyton and Butt were anthropologists conducting research in Africa during the colonial era. They died in a plane crush and I think they left some money for promising young people conducting research to receive this award annually. I was the winner of this prize in East Africa in 1965. The essay was also sent to the Commonwealth Development Corporation in Nairobi and I received an award as well. That was in 1965.The award was of books and cash money. The cash money from Makerere was Sh100 and from Nairobi I received Sh375. At that time it was quite a lot of money.

Who’s who in Tanzania: Not many people get PhDs without a Master’s degree. How is it possible that you skipped a Master’s degree course?

Prof Mshigeni: Prof Erick Dassont from Norway had arranged for me to get a fellowship from Norway which enabled me to work with him for one year between 1969 and 1970. I visited all of the shores of Tanzania with him to learn more about seaweeds. By the end of that year, I had a publication on Tanzanian seaweeds. When I went to Hawaii, I was exempted from doing a Master’s degree because I had many publications on this topic. But, of course, I had to sit for a qualification examination. I recall going with specimens of the Yukimia seaweed with the hope that I would do my PhD on this seaweed.

However, I was advised not to do a thesis on Yukimia. I was told that my work would lack originality, and so I had to select another type of seaweed that grew both in Hawaii and in Tanzania. I chose Hipnia, which was another type of seaweed for my PhD. I left Hawaii for Tanzania in 1974 and after national service I began lecturing at the University of Dar es Salaam. By 1979 I had about 40 publications. By the way, some full professors did not have even half of what I had published. That’s why they took me as an exception because in terms of publications I had more than most of other lecturers. I think it was largely because I was in a field where not much was known, so almost everything I was doing was original research.

Who’s who in Tanzania: In addition to seaweeds, you are also known for your research on mushrooms. What prompted you to research on mushrooms and why did you go to Namibia?

Prof Mshigeni: When I went to Tokyo in 1994 to receive the Boutros Boutros Ghali Award, I developed as a lecturer at the United Nations University (UNU) on seaweeds. The Director of UNU liked my work because it was in relation to the Zero Emissions Initiative, as I was converting seaweeds into crops. So, I was appointed a joint United Nations UNESCO Chairperson for Africa. Sam Nujoma requested that the project be based in Namibia. Since I was the one to head the project, I had to stay in Namibia instead of returning to Tanzania. I got some funds from UNDP. The initial budget was US$3.65 million, but there was a change in leadership at the UNDP headquarters in New York. The budget was reduced slightly and that became a challenge. To achieve the original objectives, I had to select plants which grew fast so as to realise rapid results. I chose seaweeds and mushrooms because mushrooms can be harvested within 3 months and again we were using waste that people were throwing away after planting maize and rice. Mushrooms are rich in proteins, vitamins and minerals. That’s how I took interest in mushrooms and found them just to be as interesting as seaweeds if not more. Now I can say I am also an expert in mushrooms and that is why I was elected the Vice-President of the World Medicinal Mushrooms Association.

Who’s who in Tanzania: Most people run to Europe and America for work. Why did you leave Tanzania for work in Namibia and not Europe?

Prof Mshigeni: I didn’t go to Namibia for work, but rather it was a coincidence. I received a telex, inviting me for an African Bio Sciences meeting on the issue of Biology in Africa. It was to be in Zimbabwe. I went and presented my paper. Biology should not be taught from books, the field should be in a laboratory. I gave an example of the seaweeds that we were teaching people in Tanzania with the help of the ocean. There was one professor from Namibia who was listening to me. After my presentation he approached me and asked me if it were possible for me to go to Namibia and present the same paper, as well as offer advice on how to develop Namibia’s marine resources. This was an American called Shaun Russel. Namibia was to get independence that year.

I told him I was planning to do my sabbatical in California the following year, but if it excited me enough I could probably spend my sabbatical leave in Namibia. He said they would arrange for me to get funds for the sabbatical leave. I went there for two weeks and was convinced that there were more for me to learn in Namibia than there was in California. That is how I ended up in Namibia and not US or Europe. After one year of research in Namibia, I found very many interesting things there. I invited scholars from China, Taiwan, Japan, Latin America and Norway and each of them with a topic relevant to what I had seen. For the opening ceremony I invited Minister for Fisheries Lazarus Hangula and Peter Katjavivi, Vice-Chancellor, for a closing function. They were impressed with what I had achieved in a short time. So, they made an appeal, through then Foreign Minister Benjamin Mkapa to allow me to stay a little longer. I became a part of the planning team for the new University of Namibia (1992) and my first task was to start a plan for the Faculty of Agriculture. When the structure of the university was established, there was to be a Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Research and the other for Admission and Finance. I was advised by Katjavivi to apply for the post of Academic Affairs and Research. I submitted my application and that is how I ended up becoming the Pro-Vice Chancellor for 6 years. I was later offered a job with UNDP Africa as Regional Director.

Who’s who in Tanzania: You have received many awards. Is there any that you celebrated most?

Prof Mshigeni: In 1993 I received an award of US$20,000 and gold from the African Academy of Sciences – Ciber Prize for Agricultural Bio Sciences because I was a pioneer in Africa in terms of introducing seaweed farming on the continent. In 1994 another of US$10,000 cash and business class tickets for my wife and me were sent from Boutros Boutros Ghali. This connected me with the United Nations University.

Who’s who in Tanzania: In a journey like the one you have gone through, there are many challenges. Are there any challenges that you would like to share with us?

Prof Mshigeni: It’s not easy to get to where I am without meeting challenges. Choosing between Geography and Botany was its self a challenge (laughing). I met my first big challenge in Hawaii when I was told that I would not be doing my thesis on Yukimia seaweed. It was a challenge because I had one full year of data. I was also asked to study French and German as foreign languages. Knowing at least two foreign languages was a requirement for PhD students. English and Kiswahili were out of question because English had been the medium of instruction during my O-level. For Kiswahili there is no journal published in Kiswahili which publishes scientific material.

I had to study German due to the historical link between Tanzania and Germany, and French since most of our neighbouring countries speak French. This was discouraging at the time, but I remembered our Kiswahili proverb “ukitaka cha uvunguni...” (if you want to success work hard).

So, I worked hard and passed my German and French within one and half years. The other big challenge was

when Mwalimu Nyerere was inaugurating Dar es Salaam Community College he challenged the university. He said Americans were going to the moon, while we might someday aim at reaching the moon. He wanted university efforts to be directed towards reaching out to villages. When I was a studying in Hawaii about seaweeds, the puzzle in my mind was how I would translate this knowledge into real life – reaching out to the people who needed it.

When I returned home from Hawaii the first thing was to teach our people, how to farm seaweeds. I had learnt that in Japan and China they ate a lot of seaweeds, but they also farmed them. So, I wrote a little booklet in Kiswahili “Mwali, ukulima wake baharini – na manufaa yake kwetu”. I got some little money from USAID to help experiment with some plants on how to farm seaweeds in Tanga, Zanzibar, Sumba Bay and also on Fundo Island in Pemba. These experiments meant to show the people that seaweeds were useful and could be farmed and I think the pride of my education was that I was able to translate this Biology technology of seaweeds into reaching out to the people. Today as you know it they grow seaweeds.

Who’s who in Tanzania: We believe you have people who have inspired you in life. Do you mind sharing with us some of the inspirational figures in your life?

Prof Mshigeni: I think the person who inspired me most was Prof Erick Darsont who pulled me into seaweeds. I must admit also that my Geography teacher, Prof Barry who wanted me to study Geography because of my background in science and not the “little sea plants” if I may use his words, inspired me. Prof Barry was a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society of the UK. I remember I wrote for him an essay giving reasons for choosing to study seaweeds. The title was “The economic importance of seaweeds – can these plants contribute to the economy of Tanzania?” I think it was about six or eight pages. I had read a lot about seaweeds in Japan, China, Korea, and Norway to justify why studying seaweeds was the best option. I presented it to him and after he had read through we shook hands. That was after a week since I had handed the essay to him. “I’m blessing you because what you have written is publishable,” he said. Prof Barry was editor of a Journal called The Journal of the Geographical Association of Tanzania. So, my essay was submitted for publication and that became my first publication in a Journal, the July issue of 1969. I remember I graduated in March 1969 and three months later the essay was already in the journal.

Who’s who in Tanzania: Do you remember any other persons who have inspired you in your social life?

Prof Mshigeni: Yes, my parents are the most special persons in my life. They had difficult lives and struggled hard to get school fees for me to go to decent schools. I would help them feed the cattle every day, going to fetch firewood, water and going with them to our garden. They trained us to do all types of things and also work hard, but again to have order in what we were doing. I recall whenever I was given something to do, it would be, work fast, do it well, then go and read. I studied 147 verses from the Bible when I was in Standard 4, I could recite them by heart. They were a great inspiration to me, both my parents lived to be 105 years old.

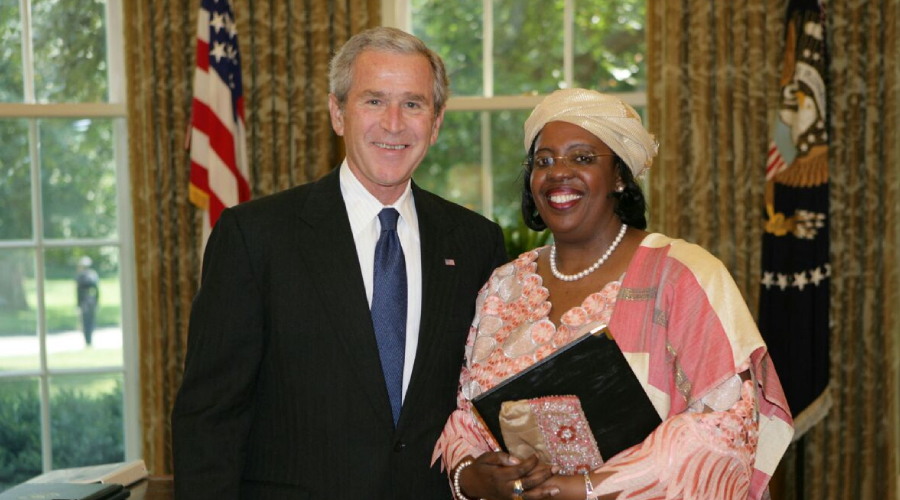

The other special person is Sam Nujoma, the first President of Namibia. He supported me when I was Pro-Vice-Chancellor in Namibia. He enabled me to get the African Universities Excellent Award in research in higher education. I think I would not have received it had it not been him. He had a lot of confidence in me to the extent that he would invite me whenever he had visiting Heads of State to see them and share some ideas about science with them. That is how I got to meet the first Zambian President, Kenneth Kaunda. This gave me an inspiration that the research I was conducting was being seen, but I think it all goes back to Mwalimu Nyerere when he said that we should reach out to the people in villages. You remember universities were called Ivory towers! I descended the towers and went to villages. I took the little I knew to harvest along the coast.

Who’s who in Tanzania: Professor, we believe you have seen it and had it all. What is your advice to the youth in this country?

Prof Mshigeni: They should keep their eyes open. There are so many opportunities that come and pass day by day. They should grab them as they come. I summarised this in one of the stories I wrote “Lighting a fire”.