Celebrating decades-long illustrious diplomatic journey of Salim Ahmed Salim

Former Chairperson of the African Union Commission, Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, described Dr Salim Ahmed Salim, as “a distinguished son of Africa and a committed Pan-Africanist, who served his country Tanzania, and the entire African continent with distinction.” The tribute is contained in a foreword for the book “Salim Ahmed Salim: Son of Africa” edited by Jakkie Cilliers.

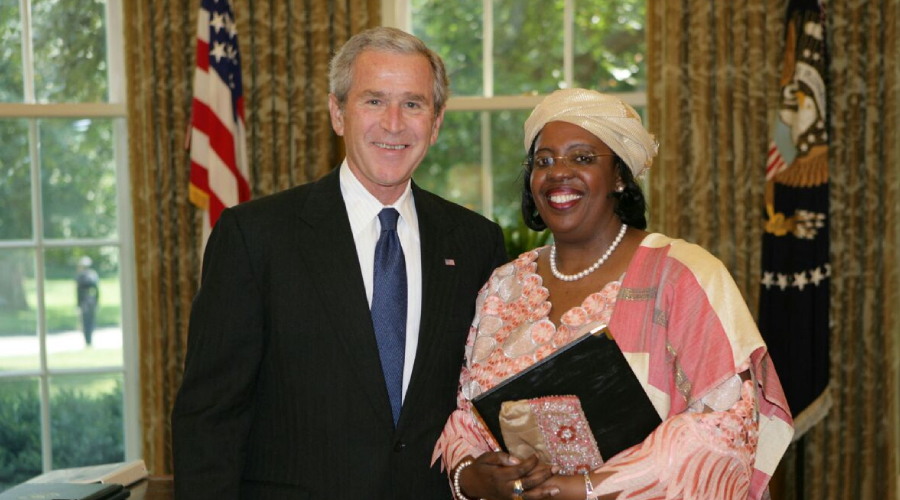

Dr Salim was appointed Ambassador of Zanzibar and later the United Republic of Tanzania to Cairo, Egypt, when he was 22 years old. After two more tours of diplomatic duty in India and China, at the age of 27 years, he became Permanent Representative of the United Republic of Tanzania to the United Nations Organisation (UNO) in New York, where he served for 12 years. He then returned home to serve on the Cabinet as Minister for Foreign Affairs, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence and finally, Prime Minister, before he was elected the Secretary-General of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. He held this position for 12 years. At the time of this interview, he was Chairman of the Board of Trustees of The Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation (MNF).

Dr Salim did his undergraduate studies at the University of Delhi and a Master’s Degree in International Affairs at Columbia University in the USA in 1975. He was awarded seven honorary doctorates by universities in Africa, Europe and the Far East. He granted this interview to Who’s Who Tanzania despite his ever-busy schedule. Excerpts:

QUESTION (Q): You are rated as the most successful Tanzanian international diplomat of your time. But there is a political side of you which is not much publicised!

ANSWER (A): After finishing my secondary education in Zanzibar, I became very busy with something else. I was deeply thinking of how to involve myself in politics aside from academic matters. At the age of 16 years, I was already deeply involved in political activities. I was a young political activist of the Nationalist Party, but later I joined UMMA Party, which we formed after a group of us decided to break away from the Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP). So, immediately after my secondary education, I was sent by ZNP to Cuba to open an office as part of a strategy to popularise and mobilise international support for Zanzibar independence cause. We named our office, Zanzibar Office. To be frank, I was not so keen to go to high school because I already had an offer to visit Cuba. For an enthusiastic politician in the making, this was a good opportunity to pursue my ambition. Remember, that was the time when Cuba was involved in a serious conflict with the USA. It was during the time after the infamous “Bay of Pigs” invasion by the USA. There are some people who said that I went to Cuba to learn how to use a gun. That isn’t so.

For me and my colleague in my company, Col Ali Mahfoudh, who became Chief of Operations of Tanzania People’s Defence Forces before joining our comrades in Mozambique to help in a fight against rebels there and Mohamed Ali Foum, the Cuba-US conflict was an enriching experience in terms of politics. The Americans under President John Kennedy, were saying that they didn’t want a communist Cuba near them and Cubans were retorting back that they too didn’t want hegemonic capitalist Americans near them. I stayed in Cuba for nine months until March 1963 during which I travelled extensively in the country. This made me know Cuban people very well not only in terms of politics, but also in their daily socioeconomic life.

Q: You had an opportunity to meet Fidel Castro at such young age. What are your memories of the great revolutionary?

A: Cubans called him “Elkabayo” (the horse). One of the great memories of Fidel Castro was when he came to New York to attend the United Nations General Assembly. At that time, I was the President of the General Assembly. It was an interesting experience. He was as friendly and as fiery as usual. His speech was one of his best speeches. I remember, to the surprise of the Cuban delegation, I decided to go and greet him at the Embassy of Cuba before he came to see me at my Office at the 38th Floor Office in the United Nations Headquarters. Both times we had great conversations and his mastery of the issues and matters of international affairs was astounding. You can’t go to Cuba without being impressed. The people of Cuba have gone through a lot of struggles to build their nation faced with many challenges. Through Fidel Castro’s leadership they achieved a lot in their struggles and most important they have always been a trusted friend in support of our struggles, African struggles. Fidel Castro Ruz, was an unwavering fighter of justice, freedom and dignity, especially for the people of Africa and more specifically to Southern Africans. Therefore, what I can say about Fidel Castro is that he did his best for his people and the oppressed people of the world.

Q: In the 2005 presidential race you were considered a strong contender, but you lost the bid. What was your reaction and how do you view party nomination processes and the presidential electoral process as a whole?

A: I think it’s important for us in the country as a political force, to see how we can improve the process and not dismiss it. We have to improve in the sense that people don’t have a ground for grumbling. My view is that we have had a relatively peaceful country and it’s important that we keep it up. We have also to find a way for dissatisfied members of our community not to be dissatisfied.

Q: There is a perception that in Africa it’s not easy to beat an incumbent President because he is better placed to rig the election. What is your opinion on this?

A: Elections anywhere, including the most advanced countries, are a problem. I think we will be making a mistake to think that our elections are perfect. They are not. There must be a genuine effort to improve the process because elections are supposed to resolve problems. Ethnic, religious, economic or whatever problems must be overcome by the political process. When it fails, then you have a bigger problem. Personally, I think CCM is a well-organised party with a strong organisational machinery, which has made it possible for the party to continue being in power. But I must say that the current trend where we have elected members leaving their parties to join other political parties is not healthy for democratic dispensation.

Q: What do you think is behind the wave of Members of Parliament (MPs) and Local Government councillors leaving opposition parties – is it sheer opportunism or exposure of opposition party weaknesses?

A: I think it’s because of the weaknesses. I can’t rule out completely the sense of desperation of how to get to power. But the mere holding of elections, genuine bona fide elections, provides an outlet to decide what people want. Elections are about determining how people should be governed and who should be their leaders. But when people start thinking of other options, they have to remember that time for military regimes, dictatorships and others wishing to be presidents for life is over now. Nothing can be permanent, and especially in politics. Those who are in power today and those who are not in power, will find it much easier to gain power by observing the rules of the game.

Q: Tanzania embarked on the process of constitutional review under former President Jakaya Kikwete, but he finished his term before the conclusion. Do you think it’s necessary to revive the process?

A: A Constitution is a document and, therefore, it can be changed. But this must not be done to suit the whims or wishes of a few people. My take is that we should respect what the people of Tanzania want. Let’s get to a point of what the people of Tanzania want. The Constitution is supposed to be made by the people and for the people. I served on the Joseph Sinde Warioba Constitutional Commission and we did our best. I’m sorry that it did not turn out to be what the effort was worth, but we have to bear in mind that the ultimate judges of this process must be our people. Tanzanians are very sensitive about this matter and none of us can take their position. The people have to decide and we should create an acceptable and enabling environment for them to decide.

Q: Let us go back to your diplomatic career path. At the age of 22 you were deployed to Cairo by President Abedi Amani Karume to represent Zanzibar in the United Arab Republic of Egypt, becoming the Tanzanian Ambassador after the Union. Then, you served in India and China before you were appointed Tanzania’s Permanent Representative to the UN. What are the highlights of your long stay in New York?

A: In my capacity as Permanent Representative to the UN at the New York Office, I was concurrently accredited as Ambassador to Cuba and High Commissioner to Guyana, Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago. Tanzania under the committed leadership of Mwalimu Nyerere we were all in the lead when it came to liberation issues being discussed at the UN. In that respect, from 1972 to 1980, I was the Chairman of the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonisation, famously known as the Committee of 24, and I was also the Chairman of the United Nations Security Council Committee on Sanctions against Rhodesia (Northern Rhodesia - now Zambia and Southern Rhodesia - now Zimbabwe) among other committees that were working on the liberation of the remaining territories that were under colonialism. In January 1976, I was elected the President of the United Nations Security Council for one month during our two-year tenure to the Council. Likewise, I became the President of the 34th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. By then, I was only 37 years old. It was a great experience. In January-July 1980, I presided at the 6th and 7th Emergency Special Sessions of the United Nations General Assembly on Afghanistan and the Middle East. In September 1980, I also presided at the 11th Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly on Development. In all these positions, I performed my duties as first a representative of Africa and the voice of the third world. I did my best to serve the interests of our continent while enabling global peace.

Q: Despite your distinguished service at the United Nations, your nomination for election as UN Secretary General in 1981 was blocked by the US Government. One account claims the rightist Ronald Reagan Administration was concerned about your ‘hostility’ to apartheid South Africa and support for Palestinian statehood. In what politics was the election shrouded?

A: The Americans, one of those ironical things, unfortunately, had determined that they would not support me, but they would not say it. They refused to say how they voted. It’s the only country with a “veto power,” which was against me. Why they were against me, they did not want to disclose it. But the actual context in the Security Council was very fascinating. The way the Security Council votes, for one to become a Secretary-General, he or she must get a minimum of nine votes, including the votes of the five Permanent Members of the Council, who have the “veto power.” There were 16 rounds of voting and, throughout, the Americans voted against me about nine times. Meanwhile, when I decided to withdraw my name from the ballot, the Chinese also voted against incumbent Kurt Waldheim until he was forced to withdraw his name too and allow for a compromise candidate and that is how Javier Perez De Cueller from Peru became the Secretary-General.

Q: At one time you were Minister for Foreign Affairs. Later, you were named the United Republic of Tanzania’s Prime Minister. Do you have any significant memories you can recall on these appointments?

A: I became Prime Minister in very tragic circumstances in April 1984, the passing away of Edward Moringe Sokoine in a road accident. It was a big blow to the entire nation. For me especially because I knew him well and respected him. We were very close. While he was Prime Minister and me as Minister for Foreign Affairs, he was so keen to follow and find out from me what was going on in the world. Among other things, during this time I continued helping Mwalimu’s efforts in bringing about the liberation of our continent.

Q: In 1989 you were elected Secretary-General of the Organisation of African United (OAU). No veto power to reckon with this time around! You served in this position for 12 years – what do you remember most from the OAU Headquarters in Addis Ababa?

A: This time around no veto power was involved, but I went through a quite demanding election process. Regionally and internationally recognised people, among them former President Benjamin William Mkapa, by then our Minister for Foreign Affairs and John Samwel Malecela, our former Prime Minister, campaigned for me. The job was quite an experience. The biggest challenge that I faced consistently was conflict, conflict, conflict and, to this day, conflict. That is the sad thing about our continent. We gained political freedom, which was turned into a vehicle for people to fight against each other. Look at what is happening in Southern Sudan! I hope the recently signed peace agreement will be respected by all parties involved, so that the people of Southern Sudan can have a government that is able to maintain peace and security. It is so sad that millions of people have been killed because of the internal conflict. When Southern Sudan gained sovereignty through a referendum, we thought things were going to change for the better. But that was not the case. We have witnessed mayhem, murder and destruction instead. But what I can say is that the responsibility of a peaceful Sudan remains on the people of Sudan themselves. Therefore, it is the responsibility of Sudanese political leaders to make sure this is achieved.

Q: Did the Darfur problem start while you were still Secretary-General of the OAU?

A: Darfur problem! No. It was after I had left. But the Southern Sudan problem, yes because it began, while I was still Secretary-General of OAU. I dealt with it for three years before I left. But later on, I became the Special Envoy of African Union (AU) on the question of Darfur. That was also a very interesting and frustrating challenge for me. The contending forces are determined to perpetuate the war. But the Darfur people are fed up with the war. We all want Darfur to remain in the Sudan and not to disintegrate. But the responsibility to achieve this remains on the Sudanese people. They should stop bitterness and oversimplifying issues.

Q: Some political analysts believe the split of Sudan and the current internal conflict in South Sudan and Darfur were fuelled by external forces, which fear the might of a united, peaceful Sudan. What is your comment on that?

A: There is some truth in that because not everybody was cheering Sudanese unity. In Africa especially, we consider what is still happening there as a setback. Because we thought Sudan would have been an example of how a nation of diverse consequences can use diversity to promote unity and development.

Q: Tanzania played a central role in the liberation of Southern Africa and Africa in general, but the contribution, made at great risk and sacrifice, appears forgotten by the young generation.

A: People should know about the liberation struggle. This did not involve only Tanzania, but a number of other African countries as well. They need to know the history. They should know that, that was the time Africa managed its affairs, by actively and effectively supporting the liberation struggle. That was a major achievement for the African continent. I think we need to educate our people and especially the youth to know where we came from. My fear is that our people do not sufficiently know about the sacrifice we have made to the liberation Struggle. Why? When you have a Mozambican being thrown out of a moving train in South Africa, it means that our people are very ignorant of the liberation struggle. Mozambique and Tanzania made so much sacrifice. Unfortunately, even some of our intellectuals lack the knowledge that the struggle was won primarily by the sacrifices of the people of Southern Africa themselves and the “Frontline states.”

Q: Tanzania and other African countries have embarked on industrialisation as a means of eradicating poverty and achieving the middle-income economy status. Is this a viable approach?

A: Definitely, yes. It is a must process. How soon is that going to be achieved? I can’t predict. It is important because through industries, that is where we will get fairer economic terms. So, the agitation for industrialisation makes sense. But at the same time, we have to be careful bearing in mind that we are striving to achieve that in order to serve our people.

Q: During your illustrious career, you worked with and you were even mentored by great leaders like the Father of the Nation (Mwalimu Nyerere), Sheikh Abedi Karume, Muammar Gaddafi and others. How do you remember them?

A: You know, Mwalimu was a giant. I can tell you that every country has great leaders who emerged once upon a time. In Egypt, they had Gamal Abdul Nasser. In Ghana, they had Kwame Nkrumah. In Tanzania, we had Mwalimu and it will take a long time before we get another Mwalimu. He was a very simple leader, modest and articulate. He argued our case as Tanzania and as Africa. He argued our case as third world, very strongly and he was respected. Those who didn’t agree with him respected him too because they knew what he was saying was coming from the bottom of his heart. So, on Mwalimu, you can’t complain that he didn’t do much. His departure was a tremendous setback, especially to the third world. We hope we have learnt what he stood for and we will work to implement what he had envisioned. What I can briefly say on Sheikh Karume is that he was a leader who really wanted to see change in this country. I had an opportunity to work with him at some point before the Revolution. I know how committed he was to the struggle to improve the welfare of our people. Whatever he did, it was always for long-term purposes. At times he acted on his own. He would go somewhere, identify a problem and act immediately to address it. He was an action-oriented leader. We will continue remembering him as a person who did his best for our country. As for Gaddafi, I will say he was a very genuine person murdered by the powers that be. They all know Gaddafi really believed in the theory of Nkwame Nkrumah, of a continental government for Africa. Gaddafi was propelling this concept of the African Government vigorously. He was also kind and generous to a number of countries, and because of his generosity, he was considered to be corrupting those countries. But he didn’t deserve to be killed the way he was killed.

Q: Before retirement, you led an extremely busy life. How did you manage to balance work and family life?

A: I am greatly indebted to my lovely wife, Amne, with whom we have three children: Maryam, Ali and Ahmed. Amne has been a very understanding wife. That is very important and quite often, she has been a source of strength for me. Even when I am in difficult situations, she would encourage and support me.

Q: What do you have to tell the youth of Tanzania?

A: The youth of this country have enormous responsibility. Why? First, they are the majority in our country and in Africa as well. They must use this majority for the most constructive purpose. I can understand the frustration they face because I was once a youth myself and so I can also understand their expectations. They need to work together and realise the value of age and gender. Our children should not think that everything was archived easily without any plan and struggle. They should know the history of our country. They have the right to pursue their dreams, but they must do so without disrupting the foundations of national unity, which transcend religious, racial, ethnic or gender considerations.